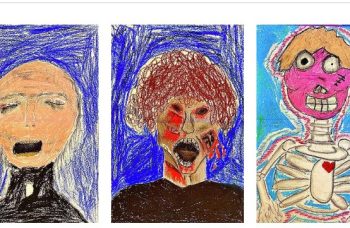

James Muriuki courtesy Nairobi Contemporary Art Institute

Anne Mwiti, Kenyatta University

Mwili, Akili na Roho (Body, Mind and Spirit) – on in Nairobi, Kenya – is a major international exhibition presenting East African painters who are key players in the modernist art of the region. Modernism in the fine arts refers to a period of experimentation from the late 1800s to the mid 1900s, a break from the realism of the past and a search for new forms of expression.

The exhibition features a group of artists from different generations who vary in backgrounds, as well as in the themes and forms of their art. They represent 50 years of East African art – from 1950 to 2000. They are: Sam Joseph Ntiro (1923-1990), Elimo Njau (1932-), Asaph Ng’ethe Macua (1930-), Jak Katarikawe (1940-2018), Theresa Musoke (1942-), Peter Mulindwa (1943-), Sane Wadu (1954-), John Njenga (1966-1997), Chelenge van Rampelberg (1961-) and Meek Gichugu (1968-).

Together they form an important cross-section of figurative paintings from Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania. Figurative art draws from the real world, especially human figures.

While modernism is most commonly associated with the western world – think Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse or Marc Chagal – these African modernist artists often critique western stereotypes about “primitive” colonised peoples at the same time as they yearn to recover pre-colonial modes of experience. This is one of the aspects that makes the exhibition so powerful. But it contains many more themes to consider that remain relevant today.

A growing showcase

The first showcase of Mwili, Akili na Roho took place in Germany in 2020. It was part of the larger context of a solo exhibition by its originator, the celebrated Kenyan-British artist Michael Armitage. Armitage is the founder of Nairobi Contemporary Art Institute – where the exhibition is currently on show. In 2021, Mwili, Akili na Roho moved to London as a continuation of Michael Armitage: Paradise Edict.

This third iteration in Nairobi expands on the first two. The initial exhibition had seven artists (with the exclusion of Njenga from Kenya, Mulindwa from Uganda and Ntiro from Tanzania). The Nairobi edition boasts a total of 54 artworks, presenting additional works from collections around the world. Notably, artworks are also borrowed from the artists’ own collections.

The exhibition focuses entirely on painting as one of the most prominent mediums of expression in art, representing a sort of history of the painting of East Africa. It’s an entry point for a deeper engagement with this history, and the enduring influence of creative ideas and art institutions from the region.

Faith and religion

For example, the idea of faith and religion is represented by works such as Ntiro’s Agony in the Garden (1950), an African representation of the story of Jesus in the Garden of Gethsemane before his crucifixion.

James Muriuki courtesy Nairobi Contemporary Art Institute

In the 1980s, Wadu took a different approach to the same subject. He paints himself as Jesus in Walking on the Water and in Give us Our Daily Bread. He tells his personal story of faith through his paintings. He attributes his success in life to God, having had tuberculosis as a young man but healing as a result of his faith.

There are also artists who have approached religion in the form of African mythology about humanity. Mulindwa did a great deal of research into the myths of the Toro people of Uganda, which influenced his art.

Land and politics

Katarikawe’s works feature cattle as symbols of life, borrowing directly from his and other people’s everyday lives. Nature and landscapes also feature prominently.

Ideas about land and politics offer social commentary throughout, about colonialism and the theft of the land.

Landscapes are also touched on by artists such as Musoke, who sought refuge in Kenya, leaving Uganda during the reign of dictator Idi Amin. Mulindwa’s large, chaotic landscapes depict a subtle social commentary on the oppression in Uganda.

James Muriuki courtesy Nairobi Contemporary Art Institute

East African art structures

It is useful, when looking at the exhibition, to also reflect on the artists’ backgrounds. Five were educated at Makerere University in Uganda, creating a school of thought of huge significance in East Africa.

These interconnected backgrounds allow reflection on the art structures and spaces that have existed in East Africa. After independence in the region, there was a short period when Makerere University, the University of Dar es Salaam (Tanzania) and the University of Nairobi (Kenya) were part of a single art school, Margaret Trowell School of Industrial and Fine Art. There was an exchange of knowledge and influences that can be traced in the body of works in the exhibition.

The other five did not receive any formal training in art. Among them, Njau was the founder of the Paa ya Paa Arts Centre in Nairobi and Musoke taught art at universities for about 25 years. Wadu was one of the founding members of the Ng’echa Arts Collective in Kenya (established in 1955 and commonly referred as the “village of artists”) and rose to prominence at Gallery Watatu in Nairobi, where Gichugu had his first solo exhibition.

So, the exhibition also demonstrates how visual art can be used as a tool to educate about history.

Creating a new space

As much as the Nairobi contemporary art scene is vibrant, with galleries selling and showcasing work, there is no museum or other space dedicated to tracking the history of the region’s art, recording it, and building content that can be viewed and reviewed over time.

The Nairobi Contemporary Art Institute has rightfully claimed this space and Mwili, Akili na Roho is an example of some important choices the gallery is making in furthering the art of the region. The exhibition is educative and – importantly – is open to schools and universities in Kenya for students to learn more.

Mwili, Akili na Roho will run at the Nairobi Contemporary Art Institute until 18 February 2023.![]()

Anne Mwiti, Lecturer, Kenyatta University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.