The pandemic has created a uniquely difficult financial situation for art institutions around the world. Reeling from social distancing and facing a “new normal” that is quite unfriendly to museums and theatres that thrive on large numbers, many are turning to assets for hope of staying afloat. The Royal Opera House in London is among the most recent to resort to such tactics with the announcement that they will sell a portrait of Sir David Webster, once the head of the ROH, painted by British artist David Hockney.

The Hockney depicts Webster in profile, sitting in a chair at a glass coffee table boasting a vase of vivid pink tulips. It was painted in 1971 after Webster stepped away following a 25-year tenure at the institution. Its commission was funded through a staff whip-round and in recent years hung at the ROH’s Covent Garden venue. Now, the work will head to the auction block at Christie’s later this month with a pre-sale high estimate of £18 million.

The ROH is the largest arts employer in the UK and is also home to the Royal Ballet. During the pandemic, it’s lost £3 out of every £5 of income, so the sale of the Hockney is part of a larger initiative, that also includes redundancies and fundraising, to ensure the ROH’s future.

Alex Beard, the current chief executive of the ROH, called the portrait’s sale “vital” in a statement, ensuring that “the proceeds will be used to ensure that the world’s greatest artists can once more return to our stages.” Beard also stated that Hockney was informed of the decision to sell the portrait, one of only a handful of commissions the artist ever accepted. While Hockney and the opera house have a “good relationship,” Beard acknowledged in The Observer that “[Hockney] does not much like it when any of his work is auctioned.”

While such decisions are coming to be the only saving graces for many institutions, they also feed into a troubling cycle that will most benefit auction houses and the wealthiest who are able to grab up museum-worthy pieces like never before as institutions try to cover their bases.

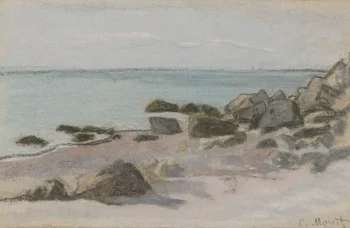

In the US, a number of museums are looking to take advantage of relaxed regulations set out by the Association of Art Museum Directors that typical ban the sale of artworks in collections to supplement operating costs. In light of the pandemic, however, the association made the decision in September to allow museums to use their collection as a means to make ends meet. The Baltimore Museum of Art, which anticipated a year of collecting works by woman artist, will instead soon send artworks by Andy Warhol, Brice Marden, and Clyfford Still to auction at Sotheby’s. Meanwhile, the Brooklyn Museum is set to liquidate 12 artworks later this month, including works by Lucas Cranach the Elder, Gustave Courbet, and Camille Corot. The Royal Academy of Arts in London has been urged to deaccession the Taddei Tondo by Michelangelo, which would effectively alleviate their financial stresses altogether. However, the RA has opted not to, stating that keeping their collection together is its “duty […] for current and future generations.”

The divide between institutions who choose to deaccession artworks and those that do not have any art to fall back on, those who feel it is a right and necessary move and those who find it abominable and irresponsible will likely only grow as cracks in the arts sector are highlighted by the pandemic. Although, as stated by Charlotte Higgins, chief culture writer for the Guardian, when the dust settles around a frenzy of artworks quickly sold in an effort to keep institutions viable, the public are likely to suffer the most in years to come as artworks, once public, disappear into private collections.