Eight years ago, Bavarian authorities searched the Munich flat of Cornelius Gurlitt looking for evidence of tax evasion. Instead, officers discovered a vast collection of works by artists like Édouard Manet, Henri Matisse, Max Liebermann, and Paul Klee. The works recovered from Gurlitt’s Munich and Salzburg homes became the centre of an investigation that many hoped would shed light on the work carried out by Gurlitt’s father, the notorious and unscrupulous art dealer Hildebrand Gurlitt. A report released by Monopol, a German publication, signaled that the research has been concluded, but it seems many questions remain unanswered.

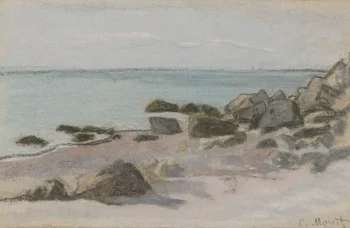

A series of essays compiled into an anthology by the name of Gurlitt Art Find: Paths of Research details the research performed by a team of experts from Germany, France, Israel, and the US, which was partially funded by the German Lost Art Foundation. Around 1,500 works were recovered in the Gurlitt trove and, according to researchers, only 14, so far, have been determined to have been looted. These works, by Liebermann, Matisse, Thomas Couture, and Adolph von Menzel, among others, have now been clearly identified and returned to the rightful owners. A further 445 artworks were determined to be “harmless,” meaning they are not believed to have been looted. Thus, around 1,000 artworks still lack a solid provenance, even after research, leaving a gaping hole in their histories as well as Gurlitt’s dark past.

According to Gilbert Lupfer, co-editor of Gurlitt Art Find and board member of the German Lost Art Foundation, researchers exhausted all avenues when working with the artworks. He also pledged that as any new information comes to light, they will investigate. Lupfer also disclosed that early on in the investigation, it became clear that the recovered works weren’t the “Nazi treasure of billions” that many anticipated. Additionally, researchers found that some works amassed by the elder Gurlitt were counterfeit and other works in the trove still have questions of authenticity looming large.

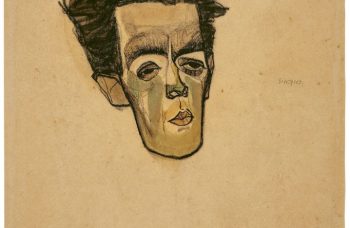

The artworks were brought together by the elder Gurlitt who capitalized on the destructive and murderous efforts of the Nazi regime, particularly during the Nazi occupation of France. Working with and for Nazis, Gurlitt forged receipts and transaction details, lied, created aliases, and altered his business records in order to acquire works, often looted or sold under duress, intended for Hitler’s unrealised Führer Museum. While doing so, Gurlitt used the situation to his advantage, creating his own private collection, which is largely believed to have been smuggled across the French border with the help of his children, Cornelius and Benita. The elder Gurlitt was exonerated of criminal collaboration in 1947 and died in a car accident in 1956. The younger Gurlitt led a reclusive life until his death in 2014. At that time, his entire collection of works was bequeathed to the Bern Art Museum in Switzerland, where his father was once the director.

While research did not yield the exact outcome many had hoped for, it shows that getting to the bottom of the cultural atrocities carried out by the Nazi regime will mean looking into private collections and the art trade alongside museum collections. “Discretion is important for the art trade,” acknowledged Lupfer. “But now you can see which long-lasting networks have existed and continue to exist.”