Five years after he dramatically attempted to smuggle a rare Pablo Picasso painting out of Spain, Jaime Botín— the ex-president of Spanish financial institution Bankinter—has been sentenced to three years in jail and lumbered with a €91.7 million fine. The hefty punishment marks a significant increase over Botín’s already substantial sentence of 18 months and €52.4 million, handed down last month. In an extremely rare move, Judge Elena Raquel González Bayón amended her original decision following a request from state prosecutors and tax authorities. The artwork in question, entitled ‘Head of a Young Woman’, hails from Picasso’s pink period and was deemed an item of “cultural interest” by the Spanish government, to whom it has now been gifted ownership.

Botín had previously tried to take the piece overseas in 2013 to sell it at Christie’s in London, only for a Spanish court to put an export ban in place. That ban was upheld in May of 2015, prompting Botín to take the law into his own hands and launch a smuggling attempt via a superyacht from Corsica to a buyer in Switzerland that same year. Island officials were tipped off to the ruse and the painting was apprehended, while Botín, who was not at the scene of the crime at the time, is now coping with the consequences of his foiled scheme.

The Botín case highlights a growing trend: Western countries are arguing that certain pieces of artwork need to be “saved for the nation” rather than sold to foreign buyers. The UK has been a particularly forceful player in this respect, although its policy has enjoyed mixed success to date – over half of items that have been hit with export bans have ended up overseas eventually regardless. Meanwhile, the whole subject has brought into focus the hypocrisy of such a stance, given that the UK’s museums—and those of other Western countries—are full of items procured by unlawful means centuries ago.

Hoarding national treasures

The Botín case is a striking example of Spanish courts taking steps to protect artworks that they deem as vital to their national identity, but the practice has become increasingly prevalent across Europe. Last September, the French art world was aflame with the discovery of a 13th-century Cimabue masterpiece in the kitchen of an elderly woman in the north of the country. After being offloaded at auction for €24 million the following month, the French government blocked the sale, designating the painting a national treasure and preventing its exportation.

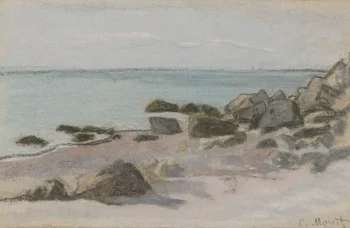

But while France and Spain made have made headlines with such “cultural interest” stories of late, the UK is head and shoulders above other nations when it comes to implementing such export bans. Prominent incidences include the case of a Peter Paul Rubens painting which is one of a scant few 17th century artworks portraying an African man in Europe, a 1773 work by Thomas Gainsborough entitled ‘Going to Market, Early Morning’ and the simultaneous introduction of export bans on famous pieces by JMW Turner and Claude Monet.

This trend towards attempting to safeguard artworks deemed as integral to British identity – even when not painted by homegrown artists – has been supported by senior politicians and prominent figures of the art scene. In 2015, Labour’s culture spokesman Michael Dugher announced his support for extending the remit of export bans from six months to at least two years, while Lord Inglewood, a former chairman of the Reviewing Committee on the Export of Works of Art (RCEWA), has also called for more stringent measures to keep Britain’s so-called “national treasures” at home.

A patchy track record

Despite this increased emphasis on protecting items of cultural interest, the policy has only enjoyed meagre success to date. In the year ending April 2014, for example, British art exports reached a record high of £11.3 billion according to a study by Thomson Reuters—a 7.6% increase from the year prior. In that same time period, 22 temporary export bans were put in place, but a mere eight of them were successful in keeping the targeted works within the British Isles.

Other investigative research paints an even grimmer picture. A report published by i-news found that almost half a billion pounds’ worth (£489 million) of national treasures have escaped the UK in the last decade. In stark contrast to that figure, a measly £97 million were saved by export ban initiatives. Given that the revenue generated by the art market continues to grow apace—in 2019, its value increased 6% from the previous year to reach $67.4 billion. With funding from public bodies such as the Heritage Lottery Fund has remaining static at approximately £15 million per annum, it’s unsurprising that many initiatives to prevent masterworks from leaving the UK have failed.

Notable examples of artworks slipping through the net include Nicolas Poussin’s ‘Ordination’, which was acquired by the Kimbell Art Museum in Texas in 2011 after the National Gallery failed to raise £15 million to purchase it, as well as Paul Cézanne’s ‘Vue Sur l’Estaque et le Château d’If’, which was lost by Cambridge’s Fitzwilliam Museum in 2015. Similar results have also been observed elsewhere in Europe, such as with a Caravaggio original which sold to a private buyer just days before it was due to enter a public auction. The export ban France placed on the piece expired when the Louvre museum passed up an opportunity to buy it, amid doubts over its authenticity.

Much ado about a Young Man in a Red Cap

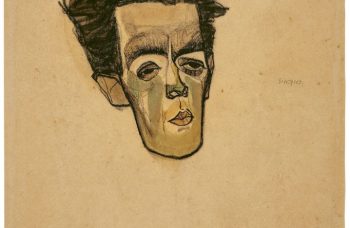

Ironically, the collector which picked up the Caravaggio—American hedge fund manager J. Tomilson Hill—has also been embroiled in what’s perhaps the highest-profile controversy surrounding an export ban. The drama concerns a painting entitled ‘Portrait of a Young Man in a Red Cap’ by Italian artist Jacopo Pontormo. The artwork, considered one of the finest examples of Florentine mannerism, first surfaced in 2008 in the private collection of the Earl of Caledon, who loaned it to the National Gallery under a gentleman’s agreement that it would not be sold during the term of the loan.

The earl threw a wrench in the works, however, when he clandestinely sold the work on to hedge fund magnate Hill in 2015 for a fee of £30.7 million, prompting the UK government to place a ban on its exportation to give the National Gallery time to raise the necessary funds to match Hill’s offer.

After several extensions of the ban period, the Gallery finally stumped up the cash in 2017 – but by this time, the financial ramifications of the 2016 Brexit referendum meant that the value of the pound had slumped significantly. Indeed, the £30.7 million initially paid by Hill was now worth $10 million less and the collector quite understandably baulked at the idea of accepting such a loss. The Gallery decried Hill for reneging on their agreement, but the American pointed out that he had already been prepared to forego the $20 million potential profit that the artwork’s subsequent increase in value would have afforded him.

The whole saga has grown arms and legs since, with the government declining Hill an export license for the piece and Hill refusing to accept a substandard price for his painting. As a result, the art world as a whole is likely to lose out; the painting may now remain in storage, where no-one will be able to enjoy its beauty. Such a sad outcome is the perfect illustration of one disadvantage of this “cultural interest” idea – but it represents just the tip of the iceberg regarding the subject’s problems.

Export bans’ downside

As well as causing stand-offs between the private buyers who are instrumental in propping up the art world and the galleries which exhibit masterpieces to the general public, designating items as “national treasures” or of “cultural interest” can have other unwanted side-effects. For one thing, encouraging sellers to only accept bids from domestic buyers significantly narrows the market, restricting trade and driving down the value of the artwork itself.

In one newsworthy example, Italian collector Elena Quarestini was unable to find a buyer for an early Salvador Dalí work due to a national court ruling that the painting must remain on Italian soil, despite the fact that the Dalí Foundation itself had made a serious offer. Italian export laws are so strict that any work currently in Italy and created by a deceased artist more than 50 years ago has to receive an export license. What’s more, the Italian government seems to take a wide view of what constitutes an acceptable justification for denying an export license—one of their reasons for keeping Quarestini’s Dalí was that the work is “very beautiful”.

A perhaps more concerning implication of “cultural interest” laws is their complete disregard for the fact that many of the artworks in question are not, in fact, a cornerstone of the country’s culture – but that of another nation or people altogether. Indeed, a recent report commissioned by French President Emmanuel Macron concluded that over 90% of African heritage artefacts are located in European museums. While Macron has pledged to begin righting those wrongs by returning a handful of Benin Bronzes to Nigeria, the British Museum has refused to even countenance the idea of following suit.

Indeed, the British Museum’s stubborn rejection of any relinquishment of the spoils of its colonial days – such Lord Elgin’s removal of the Parthenon Marbles from Greece under extremely dubious circumstances – speaks volumes about its myopia on the subject. One London-based art dealer (who wished to remain anonymous for fear of reprisal) recognises the truth of the matter: “We didn’t exactly give the Greeks or Egyptians the option to put an export ban on their antiquities to see if someone would stump up the cash to keep them in Athens or Cairo, did we?” he remarked. “Either we accept the free movement of privately-owned objects, or we don’t.”

National treasures and international treachery

Of course, there are plenty of reasons why the export bans make sense on both a financial and a jingoistic level, but it must surely be recognised that the moral quandaries raised by the situation are hard to see past. It’s all well and good for the UK to wish to keep its Gainsboroughs and its Turners on British shores, but when it comes to claiming Pontormos, Poussins and Cézannes as crucial to the UK’s national identity, alarm bells must surely start ringing… and that’s even before other artefacts like the Elgin Marbles are taken into account.

For senior British figures to lament the drain of prestigious artworks (by legal means) to an overseas buyer smacks of a hypocrisy that is as brazen as it is unbelievable. By all means, those museums and galleries which can afford to retain their prized assets should be free to do so – but not at the expense of other nations’ cultural heritage, nor with the expectation that private collectors like Hill will foot the bill. Prudence in safeguarding these alleged national treasures is welcome, but perspective in viewing the bigger picture with regard to the sensibilities of other nations is surely a more equanimous and equitable endeavour.