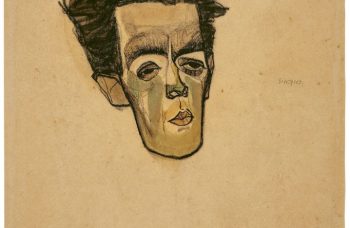

An Italian gardener made global headlines last month after stumbling across what appears to be the second most sought-after piece of stolen artwork in the world. The unassuming groundskeeper made the incredible find while maintaining the estate surrounding the Ricci Oddi modern art gallery in the northern Italian city of Piacenza, where the painting – an incredibly rare work by Gustav Klimt valued at an estimated $66 million – had hung 23 years previously.

While warmly welcomed by the gallery’s owners, the discovery throws up almost as many questions as answers, with both the identity of the thieves and the painting’s movements in the intervening two decades shrouded in mystery and confusion. Such chaos is sadly an all-too-common symptom of the art world, where theft and forgery are disturbingly pervasive practices. As the largest unregulated industry on the planet, it’s perhaps unsurprising that art-related crime is the third most lucrative illicit trade behind only drugs and weapons. According to a 2014 report from the Fine Art Expert Institute, over half of all art is either fake or mistakenly attributed.

Obviously, this kind of duplicity has huge financial ramifications not only for private buyers duped into forking out millions for a phony artefact, but also for the galleries hoodwinked or ransacked by unscrupulous actors and for the public deprived of enjoying the genuine articles. With that in mind, museums and law enforcement agencies have been pursuing more stringent and sophisticated methods of protecting their assets and tracking down guilty parties, but the prevalence of shady practices suggests a more serious problem than insufficient security systems. Instead, it may be the very nature of the beast which makes the art world so prone to artifice and illegal activity.

Once was lost, now is found

Tests to verify that the recovered Piacenza painting is, in fact, the long-lost Klimt are still ongoing, but the artwork is strongly suspected to be The Portrait of a Lady—the only known example of a double Klimt (one painted over the top of a pre-existing canvas). It was found in a cavity in the wall of the gallery itself, sealed inside a vault and covered with vines. Remarkably, the painting was in immaculate condition, something not consistent with it having spent over 20 years inside a damp and moldy alcove. That’s not the only piece of the case which has investigators scratching their heads, however. Italian authorities are adamant that, immediately following the original theft in 1997, they had combed every inch of the gallery’s grounds, making it highly unlikely they could have missed such an obvious hiding place.

To muddy the waters further, in 2016 an unnamed informant claimed involvement in the robbery, stating that he and a gallery insider had carried out the original theft in two stages. The elaborate plot the purported thief described sounded like something from a film: first, he insisted, he had stolen the real Klimt unobtrusively, replacing it with a high-quality copy. An upcoming exhibition, however, would have drawn unwelcome scrutiny to the painting—and so the thief returned to the gallery and stole the copy as well.

Though the self-declared brigand claimed to have sold the painting long ago for a large quantity of cash and cocaine, he also insisted, bizarrely, that the painting would be returned by the 20th anniversary of its disappearance. February 2017 came and went without the Klimt’s return—but now the prodigal painting has mysteriously resurfaced, spawning a host of new theories. As well as the inscrutable idea that some benevolent soul surreptitiously returned the painting to the gallery for reasons unknown, there’s also the possibility that it was stashed onsite to make the escape easier at the actual time of the crime, then later abandoned – although that doesn’t explain how it has remained in near-pristine condition or how the police missed it at the time.

Adding still further layers to the tangled puzzle, the gallery’s director at the time of the 1997 theft, Stefano Fugazza, wrote in his diary just days before the theft that he had contemplated a scheme where he—in cahoots with the police—would have pretended the painting had been stolen in order to drum up additional press for the gallery’s upcoming exhibition. Fugazza, naturally, now insists that he gave up the plan: “But now The Lady has gone for good”, he later wrote, “and damned be the day I even thought of such a foolish and childish thing”.

While the whole saga might seem more fitting for Hollywood than real life, such tall tales are not unheard of in the art world. After all, one of the most famous artworks of all time – the Mona Lisa, visited by some 30,000 people a day – only gained its current prestige after being pilfered in 1911. Indeed, such was its relative obscurity beforehand that it took the Louvre authorities 28 hours to notice its absence, while the Washington Post article which originally carried the story mistakenly included an image of the wrong painting.

Elsewhere, another high-profile heist involving five paintings lifted from the Schloss Friedenstein in 1979 East Germany has recently come to a satisfying but stupefying conclusion. For forty years, armchair sleuths and public authorities alike puzzled over who had executed the daring and perplexing art robbery of Gotha—in which a pair of thieves apparently scaled the castle walls, passing by even more valuable paintings to spirit away five carefully-chosen Renaissance masterworks. Suspects included palace staff, a famous family of trapeze artists, and the Stasi colonel Alexander Schalck-Golodkowski.

With a collective value of over €48 million, the paintings—including a self-portrait by Anthony van Dyck, a landscape by Bruegel the Elder, and one of Holbein’s most-admired court portraits— were sorely missed from the castle museum. A few months ago, however, they were returned to the town after furtive negotiations between its mayor and a lawyer claiming to be in contact with “clients” in possession of the artwork. The story provided by those “clients” to account for the paintings’ whereabouts was deemed “quixotic, unverifiable and implausible” by the authorities and investigations are still ongoing.

The ubiquity of art crime

These kinds of audacious raids are not just a thing of the past, either. Another of the world’s most famous paintings, Edvard Munch’s The Scream, was stolen not once but twice, in 1994 and then again in 2004. In 2010, the so-called ‘Spiderman’ cat burglar made off with five paintings valued at a cumulative $115 million from Paris’s Museum of Modern Art; though the culprit was caught, the artworks have never been recovered. In 2017, a giant solid gold coin weighing over 100kg and measuring more than half a meter in diameter was stolen from a Berlin museum.

2019 has even seen its fair share of scandals. In September, a solid gold toilet was the unorthodox target in a successful raid at Blenheim Palace in England. More recently, an audacious attempt to steal two priceless Rembrandt paintings from a south London gallery was narrowly thwarted after a police officer found the thief hiding in bushes outside. The suspect effected his escape by spraying the officer in the face with an unknown substance, but in his haste, he thankfully left his booty behind. Unfortunately, one museum in Dresden was not so lucky, as bandits escaped with an estimated €1 billion of art and jewelry – the biggest heist of its kind since WWII.

While such notable incidents dominate the front pages, they represent the merest tip of the iceberg when it comes to crime in the art world. Interpol catalogs around 50,000 stolen works of art per year and the black market trade for illegal items is estimated at between $6 billion and $8 billion annually. Credible forgeries of artists like Dalí and Ernst are so prevalent that buyers are especially wary of purchasing their works, but it’s not just paintings that are subject to artifice and chicanery.

Indeed, sculptures are more popular targets than pictures, while even valuable curios like Fabergé eggs are prime real estate for forgers. According to the world’s foremost expert on the subject, 99% of the artefacts brought before him for authentication are fake. In one particular jaw-dropping anecdote, he reveals that one wealthy collector Middle East brought him a collection he had acquired for over $60 million – every single one of which was an imitation. The collector hushed the findings, preferring to save face rather than save fortunes.

Searching for solutions

It’s this predilection for secrecy and a stiff upper lip that hamstrings the art world in clamping down on the parasitic criminals which feed off it. As well as keeping schtum about when they’ve been deceived, many collectors rarely inquire about the provenance or history of items they wish to obtain, as per standard art world protocol. In no other business transaction in the world would a buyer fork out millions of dollars without receiving documentation or assurances that his purchase is legitimate and legal.

In an attempt to alleviate the difficulties this places on recovering stolen pieces, one solution which is being considered is to offer an amnesty for any duped investors who end up with stolen artwork on their hands, alongside a reward for its safe return. Given that items generally sell for a mere fraction of their actual value on the black market – often around 10% of their true worth – a 5% deal-sweetener could be a small outlay for museums and galleries looking to recover their possessions and recoup some of their stolen wealth. Of course, such fees must only ever be paid to deceived parties and not deceiving ones, for fear of setting a dangerous precedent that the art world is ripe for extortion.

Some may argue that precedent already exists. Given that art theft is such a widespread phenomenon, and that law enforcement is so hopelessly equipped to deal with it, it’s difficult to disagree. At present, there is just one art crime officer for every 21 million citizens living in the USA, making for a total of 16 dedicated to rooting out the practice; in the UK, there are just 2.5 (one only works part time). Bolstering the boys in blue may actually even prove counterproductive, though, if one analysis is to be believed. Experts on the theme contend that beefing up the police could disincentivise museums to implement their own security, resulting in more thefts overall.

But whether it’s enhancing protective measures to prevent the crimes from happening in the first place or investing in better methods of tracking down transgressors after the event, both of these solutions appear to treat the symptoms of the issue, rather than its root cause. The truth is that art crime is so rampant due to an environment which encourages confidentiality to the point of clandestineness, making things ever so easy for those operating outside the law.

Symptoms of a broken system

Distraught at the unceasing tide of high-profile art thefts, the art world is trying to come up with innovative solutions, including the prospect of introducing technology where manpower has failed. The use of blockchain to create an online and immutable log of artworks from their point of origin to that of sale could help to improve transparency and guarantee authenticity in the whole process, all the while still enshrining the anonymity of involved parties.

It’s a suggestion that’s certainly worthy of consideration. Given that human supervision seems utterly incapable of adequately managing an industry that’s thought to be worth over $67 billion per annum – and that in fact, actually seems predisposed towards facilitating corruption – it might be time to let the automatons take the reins. The 90% of art theft victims who never recover their stolen items would surely be thankful for the change.

The surest solution, however, would be a paradigm shift in the art world’s culture. Everything about the trade of fine art, from the unwritten etiquette which demands all involved do not ask questions, to the huge vaults and freeports set up to ensure works accumulate value even as they gather dust, to the almost complete lack of regulation governing the industry, is conducive to oiling the cogs of a criminal operation. Unless there is a fundamental change in how traders, collectors and middlemen carry out their business, it’s difficult to envisage a future where forgeries and thefts do not continue to proliferate.