In the wake of Prince Andrew’s controversial and ill-advised BBC interview, the British royal family has struggled to fend off unwanted media attention over his past and present conduct. The beleaguered prince braved a television appearance in an attempt to stamp out the flames of suspicion surrounding his relationship with disgraced financier and convicted sex offender Jeffrey Epstein, but only succeeding in fanning them further. After a swath of universities and charities distanced themselves from him, the Duke of York was forced to announce that he’s stepping back from royal duties until further notice.

However, Andrew isn’t the only royal to have become embroiled in a problematic situation of late. His brother Charles, first in line to the throne, appears to have been ensnared by a massive art forgery scandal. Several paintings at Dumfries House, the headquarters of the Prince of Wales’s Charitable Fund, have been removed from public viewing over concerns regarding their authenticity. Once thought to be genuine originals by artists such as Monet, Picasso and Dalí, the provenance of the art was called into question when convicted art forger Tony Tetro claimed them as his own work.

The revelations over the Dumfries House paintings not only compound what has been a difficult few weeks for the royal family—the Queen herself reportedly gathered her children for an emergency meeting against the rapidly expanding scandals—but also draw attention to the grey areas of morality and illegality that plague the art world. Tetro claims his works were only ever intended as “reproductions” rather than forgeries, but when they are being displayed as legitimate originals (even when no money has changed hands), where do we draw the lines between what is legal and what is ethical? What is the future of an art world whose integrity is under threat from the very secrecy and obscurity intended to protect it?

Royals under siege

Prince Andrew’s calamitous decision to tell his side of the story has prompted criticism from almost all quarters, with a poll conducted by popular daytime show This Morning revealing that 81% of viewers believed he should retire from his royal duties as a result – and he duly obliged days later. Perhaps one tiny silver lining to the whole sordid affair is that it has overshadowed another embarrassing story involving Prince Charles and the artwork on display at Dumfries, the stately home in the Scottish Lowlands that the Prince of Wales purchased in 2007 alongside his charitable foundation. Specifically, the Prince’s Foundation was forced to admit that several paintings had been removed and returned to their owner due to doubts over their legitimacy.

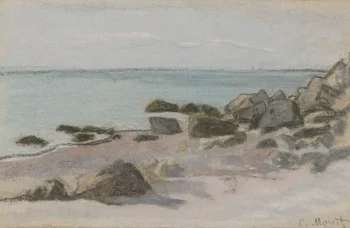

At the centre of the scandal are three paintings believed to have been created by Monet, Picasso and Dalí. Part of a 17-set collection on a 10-year loan at Dumfries House from recently-bankrupted ex-billionaire James Stunt, the artworks were reportedly insured for a cumulative £104 million. However, American forger par excellence Tony Tetro has come out and alleged that Stunt commissioned him to create the reproductions for his own personal collection, amid suggestions that the latter may have been looking to sell one or more of them to pay off his own creditors. Stunt, the ex-husband of Formula 1 heiress Petra Ecclestone, refutes the claims, stating unequivocally that “none of my stuff is fake”.

Authenticity is in the eye of the beholder

Conflicting accounts abound. According to Stunt, the artwork all received official authentications from the prestigious Wildenstein Institute in France. The Wildenstein, meanwhile, has insisted that it never looked at the works. Complicating the drama still further, James Stunt’s offices sent allegedly fraudulent emails about two works supposedly by Salvador Dalí. The emails were sent under the name and address of Nicolas Descharnes, the world’s foremost expert on Dalí—who now says that not only did he never write the emails, it took him less than fifteen minutes in front of the “Dalí” to realise that the painting was a fake.

Tetro himself, meanwhile, counters that not only were none of his works created with the intention to deceive or pose as genuine originals. What’s more, the one-time forger has insisted that he took concrete steps to ensure that his copies would never stand up to professional scrutiny for a second—as Descharnes’ examination seemingly confirmed. For example, the modern pigments he uses are immediately distinguishable from older materials by a trained eye, while the canvas differs in its pliancy and the stretcher bars carry stamps, watermarks and other indicators of their past history.

Tetro, who declined to comment for this article, maintains his labours are only ever meant to be enjoyed in private settings, allowing buyers to hoodwink their friends or but not profit financially from the deception. When it emerged that Stunt was considering the sale of an unnamed Monet to alleviate his insolvency issues, Tetro allegedly suspected foul play and blew the whistle. That decision was perhaps prompted by the events of 1991, when he was charged with 38 counts of lithograph forgery and 29 counts of watercolour forgery.

After serving a six-month prison sentence, Tetro returned to doing what he does best – creating close replicas of the work of other artists. Things aren’t quite the same anymore, however. For one thing, Tetro has vowed to be more upfront in his dealings, making it clear that his works are not original Dalís or Picassos. Admittedly, this newfound commitment to transparency wasn’t all altruistic—the court order that allows Tetro to continue painting also requires him to sign all his works under his own name, making him the only living American artist to work under such a condition.

Nor is that the only thing which has changed. In one interview, Tetro highlighted the gap between his former life in the lap of luxury and his post-prison reality. “I used to have my suits handmade by an Italian designer”, he lamented. He fondly recalled his old arsenal of flashy cars—two Ferraris, a Lamborghini Countach, and a Rolls-Royce Silver Spirit—in sharp contrast to the rented Mercedes he drives around in now. Where once he lived in a triplex wallpapered with lizard skin and celebrated his birthday alongside hundreds of guests at lavish white-tie galas, by 2000 he lived in a hotel room and celebrated his birthday alone in a bar by sticking a single candle in a glazed doughnut.

Lifting the lid on artistic deception

Tetro’s initial prosecution came at a time when the authorities were making inroads into the illicit underbelly of the art world. Between 1980 and 1987, over £750 million worth of fake Dalís alone were found in galleries across the US. Meanwhile, in the months leading up to Tetro’s arrest, art broker Frank de Marigny was sentenced to 30 months in jail and gallery owner Mark Henry Sawicki was arraigned on charges of art forgery and grand larceny in March 1989. Indeed, it was Sawicki who gave evidence against Tetro in exchange for a more lenient sentence, thus allowing detectives to capture the man dubbed “the single biggest forger in the United States”.

The circumstances of Tetro’s arrest—Beverly Hills police wiretapped Tetro’s condo before storming inside and confiscating hundreds of pages on which Tetro had replicated the signatures of his favourite artists—were suitably dramatic for one of the 20th century’s greatest forgers.

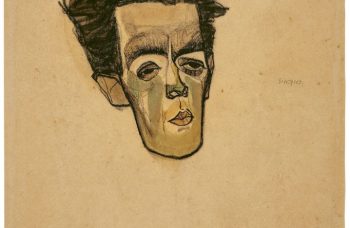

Even amongst the rarefied art world, Tetro is a fascinating character—one Californian art dealer remarked “He was just a brilliant mind that went astray—a Frankenstein”. By all accounts an incredibly talented artist, Tetro admits that he never had any interest in painting his own works. Instead, he devoted enormous amounts of energy into making the perfect copies. Tetro went to huge lengths to emulate the artists he admired—he would buy old canvases to paint over, so that his paintings would more closely resemble Old Masters. When he produced a forgery of a European artwork, he travelled to Europe to buy art supplies for added authenticity. “If you’re going to do something, why not do it right?” Tetro once remarked. “Why use other paper when I could use the paper that Chagall used or the same stretcher bars Picasso used. If not, then you’re not doing it properly.”

Admirable though Tetro’s dedication to his craft may be, it threw a wrench in his legal defence that he had never intended his paintings to be passed off as originals. In his hearing, Tetro claimed that his own actions in recreating the paintings did not constitute a crime and that the blame lay with those profiting from his proficiency. Admitting that he felt some pride at his work hanging surreptitiously in museums and galleries alongside the world’s greatest artists—one expert told the BBC that “there’s probably a Tony Tetro in every major museum in the world”—Tetro nevertheless argued that the art dealers who passed off his works as real were guiltier than he was.

“If you knew how many times I got screwed by art dealers”, Tetro told a journalist. “They never paid me up front, I was always commissioned. They made a fortune and I got arrested […] for every dollar I made, someone else made two or three times that amount”.

Such protestations were not enough for Tetro to escape a brief stint behind bars, and though he has since taken steps to make it clear that his work is intended as an homage rather than a forgery, the art world has not made similar progress in addressing the rampant impropriety which stalks its own corridors. Indeed, if anything the problem has deepened in the intervening decades, with counterfeiting and artifice all too commonplace.

The nature of the beast

The fine art world is a unique milieu, shrouded in secrecy and characterised by insider knowledge and often-exorbitant financial transactions. The identities of both parties in any deal are frequently kept anonymous to enhance the security of the assets in question, but any benefits of this opaque infrastructure are perhaps offset by the opportunities for skulduggery that they create. Stories of criminal dealings in the art world are abundant.

Take the tale of gallery owner Lawrence B Salander, for example. Salander has been dubbed the “art world’s Bernie Madoff” for the incredibly elaborate schemes by which he bilked dozens of victims out of some £90 million. Salander, who one victim described as a “sly, manipulative sociopath, a con man with no soul”, spent decades carefully cultivating friendships with artists and collectors—only to sell their paintings behind their backs, peddle the same artwork to multiple buyers, falsify records and pocket huge profits to keep up his lifestyle of jetting around on private planes. The fundamental tenets of the art world—the tight relationships between dealers, collectors, artists and gallery owners, as well as its veil of opacity—gave Salander precisely the opening he needed to carry out his extensive fraud.

Opportunities to take advantage of the secrecy and close-knit nature of the art world are even more plentiful for those skilled with the brush. Tetro may be one of the most prolific and famous forgers in the world, but he’s far from alone. In the UK, the Greenhalgh family from Bolton peddled dozens of forgeries to museums, collectors and other unsuspecting buyers between 1989 and 2006, eventually earning Shaun Greenhalgh five years in jail for his troubles. John D. Re found notoriety in 2012 when he was arrested for selling more than 60 fake Jackson Pollocks on eBay for a cumulative £1.6 million over nine years, while painter Mark Landis amused himself for nearly three decades by fashioning meticulous copies of works by the Old Masters and donating them to museums. Like the controversy currently unfolding at Dumfries House, no money ever changed hands and so Landis escaped prosecution, but his antics underscore the frailties of a broken system when it comes to artistic integrity.

Blurred lines

Landis might be the most notable counterfeiter never to have committed an actual crime, while Tetro’s recent stint in the headlines raises difficult questions about the relationship between legality and ethics in the art world. How different does an artwork have to be to be safely considered a reproduction or pastiche rather than a forgery? What happens if the paintings aren’t sold as originals, but lent out under that guise (as appears to have occurred in the Prince Charles case)? Who shoulders the blame when a reproduction hews too close to the original and morphs into a forgery, as must inevitably happen on occasion?

In seeking to protect themselves from criminal activity and unscrupulous operators, those working inside the art bubble have cocooned themselves within the confines of confidentiality. However, that self-same climate of clandestine behaviour has helped to foster immoral activities under their very noses, and without a robust infrastructure in place to police them or a fixed and well-defined boundary between rectitude and wrongdoing, the art world is in danger of becoming an incubator for iniquity.

Of course, to suggest that this is a new development would be ingenuous in the extreme. As far back as the 15th century there are accounts of artists as celebrated as Michelangelo kickstarting their careers through forgery, emphasising how the quickest route to material success has always often been pursued at the expense of loftier ideals. But with the case of Tetro, Stunt and the royal family, it’s less clear where the blame should be directed – or even if any is appropriate in the first place, given the myriad grey areas of the art world’s current rules of engagement.