Following William Blake’s rather unsuccessful exhibition in 1809, the Examiner reported his works to be ‘[a] farrago of nonsense, unintelligibleness, and egregious vanity, the wild effusions of a distempered brain.’ Things could not be more different for Blake’s recently opened exhibition at Tate Britain, the largest retrospectives of his works in nearly 20 years. Simply titled ‘William Blake,’ the exhibition puts more than 300 works before viewers as they follow the printmaker’s career chronologically.

Entering the exhibition, Albion Rose (c. 1793) stands alone greeting each visitor, setting the tone for the exhibition. Depicting Albion, which in Blake’s self-made mythology usually represents England, a nude figure stands, arms outreached against a sky that resembles a colour wheel. The painting has been interpreted in more ways than you can count (which, with Blake’s works, isn’t abnormal in any way) and preps visitors for the fascinating, anti-‘normal’ works to come. The curators wisely point out that the point of the exhibition isn’t to explain what Blake intended in his works but instead to consider how his work was experienced and perceived.

Beginning with works from Blake’s formative years, his stylistic tendency for the ultra-muscular, Michelangelo-esque drawings, engravings, and paintings he would become synonymous with is apparent from the onset. Alongside a few works by contemporaries and those of his younger brother, Robert, Blake’s free-spirited, and at times, radical ways of thinking begin to crop up early on. Soon enough, visitors are immersed in Blake’s world.

To show the books that Blake has become known for, the curators of the exhibition pulled some apart to give a complete view of the folios while leaving others together allowing visitors to see the pages in situ. The Tyger, from Songs of Experience published by Blake in 1794, is one of the first poems of Blake’s visitors come across. The poems is followed by each page of America a Prophecy, where Blake’s incessant detail mixes with the words he painstakingly engraved backwards as he’d taken on the relief etching process. By using the intricate process, Blake gained the freedom to create his own fonts to mesh with his illustrations as opposed to using tradition type sets.

Moving forward, we see Blake’s progression, working for commissions to make a living. Alongside a number of prints commissioned by a number of his patrons, including Thomas Butts, John Flaxman, and George Cumberland, are the amount Blake was paid for his etchings. In doing so, the exhibition highlights how Blake dependent upon the support of his patrons who, while more well-off than Blake, were drawn to his unconventional works. Unlike some of his contemporaries, Blake’s eccentric tendencies and dislike for many things, from science to slavery, kept him out of the mainstream during his life.

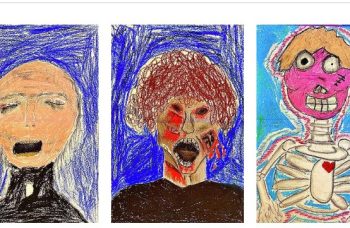

From there, each room of the exhibition shows Blake’s more developed and more critical take on his subjects. Newton (1795-c. 1805), part of a series of eight commissioned paintings, shows a bizarre scene of the scientist making calculations at what feels like the bottom of the ocean but it jives with Blake’s anti-science views. Interestingly enough, that painting became the inspiration for Eduardo Paolozzi’s 1995 sculpture by the same name commissioned by the British Library that can still be found in their courtyard today. Scenes from John Milton’s Paradise Lost and Dante’s Divine Comedy bring to life images that would have been equally inviting and terrifying to the likes of the 19th century England and beyond. A uniquely comical Cerberus (1824-1827) hangs near Blake’s The Ghost of a Flea (c. 1819-1820) showing his whimsical take on both serious beliefs and images conjured in dreams, respectively.

All in all, the exhibition is a fantastic showing of works by Blake, who never saw the fame he now holds. Ending with Ancient of Days (1827), ‘William Blake’ leaves you wanting to see and know more about the artist and the works he created.

‘William Blake’ is on view at Tate Modern until February 2nd, 2020.