The short answer: no, not really, according to new research.

Mona Lisa’s gaze, or what has been called the Mona Lisa Effect for years, is the feeling that no matter where you move in relation to a figure in an artwork, the eyes in the image follow you. Earlier this year, though, scientists debunked the myth of her eerie gaze finding that the famed portrait ironically is not a true example of the Mona Lisa Effect.

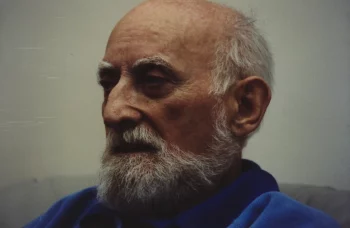

Professor Dr Gernot Horstmann of the Neuro-Cognitive Psychology research group at Bielefeld University Department of Psychology and the Cluster of Excellence Cognitive Interaction Technology (CITEC), is an eye movement specialist and was one of two researchers who recognized the flaw in the effect’s name. In the study, Horstmann states: ‘People are very good at gauging whether or not they are being looked at by others. Perceptual psychology demonstrated this in the 1960s. People can feel like they’re being looked at from both photographs and paintings – if the person portrayed looks straight ahead out of the image, that is, at a gaze angle of 0 degrees.’ However, in the Mona Lisa, her eyes stare ever so slightly to the side, about five degrees from a normal eye-to-eye gaze, thus giving the feeling that she’s looking more directly at your ear. So, while the Mona Lisa may still appear to track you around her gallery in the Louvre, she doesn’t exemplify the true Mona Lisa Effect.

To test the painting’s effect, Horstmann, along with Dr Sebastian Loth of the Cluster of Excellence CITEC, worked with a group of 24 people and a computer to determine her line of sight. They used a ruler to track the Mona Lisa’s gaze in relation to each of their test subjects while sitting in front of the monitor at different distances. Using 15 different portions of the painting, Horstmann and Loth also tested how the gaze influenced the test subjects. In all, they collected more than 2,000 samples that almost unanimously indicated that the Mona Lisa’s gaze looks more to the viewer’s right side.

‘Curiously enough, we don’t have to stand right in front of the image in order to have the impression of being looked at – even if the person portrayed in the image looks straight ahead,’ said Loth. ‘But with the Mona Lisa, of all paintings, we didn’t get this impression

Other paintings that do the Mona Lisa Effect more justice, though, include:

Rembrandt’s Self-Portrait in a Velvet Beret painted in 1634;

Frans Hals’ Laughing Cavalier painted in 1623;

And perhaps most eerie, Gustave Courbet’s The Desperate Man painted around 1843.