On February 3rd in Princeton, at the Institute for Advanced Study, Irving Lavin, one of the most important art historians of our time, passed away. For many years he occupied the Institute’s illustrious chair in art history which had previously been held by Panofsky (whose Three Essays on Style he submitted to Le Promeneur). According to one of his colleagues, even at the advanced aged of 91, Mr. Lavin still had “an active mind and a youthful curiosity”.

Irving Lavin was born in 1927 in Saint-Louis. He later completed his doctoral thesis on Bernini at Harvard. The apprentice very quickly proved his worth as an art historian and he won the Arthur Kingsley Porter Award for young researchers three times – which prompted a change in the rules! Bernini continued to remain Lavin’s favourite subject and one which would bring him the greatest fame. For half a century, he was devoted to building the collection of images sculpted by the maestro assoluto of Roman Baroque. Yet his contribution to the understanding of Bernini’s genius is far greater than the number of pieces he acquired. Lavin successfully/wonderfully showed how, more than a sculptor, Bernini was a composer (or an “editor”, as Giovanni Careri would later clarify). Playing with an extraordinary instinct and a unique knowledge of material textures, colour refinements and the direction of light, he constructed spaces where everything, including structural, decorative elements, panels, paints, busts and draperies, were put to good use to create an enduringly visible and flattering project. And that’s not the first or only reference to theatre: Lavin had justly criticised the reliance on the term theatricality used by too many pundits from the press.

He combined an unquestionable “eye” with a profound knowledge of religious and intellectual circles where pieces were created and without which there would be no art history. That is evident in one of his last major essays, written just prior to his retirement, Carravaggio e La Tour : la luce occulta di Dio (2000). In his analysis of The Tears of Saint Pierre of La Tour (Cleveland) and three paintings by Caravaggio, Lavin stresses the importance of idolization in the painting by drawing on many lectures in theology from the 1600s. He also brilliantly demonstrates the strict relationship between art history and the history of ideas, a relationship that he gladly supports.

The Italians, touched by the devotion of this overseas tribute, did not object to the recognition that Lavin brought them. He was already laden with countless titles and awards – the most prestigious probably being his induction as a foreign member of l’Accademia dei Lincei. For the American scholar, that honour was magnified a hundredfold by a clear love of Rome and other major centres of art in Italy. Lavin should not, however, be dismissed as “just” a Renaissance and Baroque scholar. His interests, shared by his wife Marily Aronberg Lavin, an art historian herself, covered a fairly extensive field, from tardo-antique mosaics to today’s art. He had written on Picasso and Pollock as well as Frank Stella and Frank Gehry. Yet despite all the accolades, the French public still knows very little about Lavin’s work which has rarely been translated (with exception given to the excellent University of Avignon Press which had published an original conference essay in 2009) but nevertheless is among the most important in its field. Will the minimal tribute of making his greatest volumes more easily accessible be, as is often the case, a posthumous one?

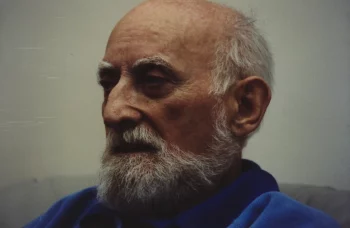

Photo IAS.