This summer, an Israeli exhibition, “Stolen Arab Art,” presented contemporary video works by leading Arab artists without their consent. Curated by Israeli artist Omer Krieger, the exhibit inaugurated the launch of the new Tel Aviv gallery, 1:1 Center for Art and Politics, and promptly caused an uproar. Was the show a publicity stunt, an act of aggression, or a trenchant critique? By attempting to highlight the oppressive conditions of the nation-state—such as the policing of borders and the hoarding of property—did the exhibit only end up reproducing these conditions, to a damaging effect?

“The works in the exhibition are being shown in Israel without the knowledge of the artists, with actual knowledge of this act of expropriation,” the exhibition text read. Works reportedly included Walid Raad’s The Atlas Group Project (1989-2004), Wael Shawky’s Cabaret Crusades (2010-15), and a piece by Akram Zaatari. The videos were screened without disclosing the names of the artists, who have not shown their work in Israel due to the political situation. In the epigraph to the exhibition text, the curators quote the French anarchist Pierre-Joseph Proudhon’s 1840 tract, “What is Property?” to further call into question: who owns culture?

The goal of the show, according to the organizers, was to protest cultural boycotts against Israel and create greater dialogue between the Jewish state and the Arab world. Earlier efforts to approach artists, they said, were met with silence. “This exhibition has been preceded by our many attempts over the years to establish contact through art with the local Arab world and the Middle East in general. It never worked for us,” Adi Englman, the gallery’s director, told Calcalist. The Academic and Cultural Boycott of Israel is part of the Palestinian-led Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) campaign to end Israeli settlement in the West Bank.

In an email, Krieger called the exhibition a “political performance” that “demonstrates the strange relation between the very active Israeli government (legislating, shooting demonstrators, putting artists in prison), and the feeble, passive and uninspiring acts of BDS supporting artists.” Krieger is a prominent figure in the Tel Aviv art scene whose work, which has included installing broadcasting stations in public squares and restaging mass riots, engages ideas of citizenship, spectacle, historical memory, and the state. “Stolen Arab Art,” he believes, was a more potent form of protest against the actions of the Israeli state than other less provocative shows.

Presenting the work without their knowledge, Krieger asserts, was also for the protection of the artists. “When we opened this center, we planned an exhibition with a young artist from Gaza whom I’ve been in touch with for several years. But in the last moment, out of fear for his life, he decided not to go through with it,” he told Haaretz.

The exhibit incited immediate public outcry. “What is the point of being a thief and so proud of your act!” Shawky, who threatened legal action, told Middle East Eye. Many took to social media to protest what they viewed as an act of exploitation. An editorial by Israeli art magazine Tohu stated, “The occupier robs and then orders the occupied to participate in a discussion. The fact is that discussions of the kind the show aims at occur all the time without coercion, cheating, or overheated self-serving publicity.” A video of the opening reception streamed from the gallery’s Facebook account shows the Palestinian artist Raida Adun confronting the exhibition’s curators. “This is beyond shameless. It is a total lack of respect to artists who have never given their consent to this. You are endangering those artists’ lives and careers,” she is seen saying.

Was the show an effective political commentary, a true generator of dialogue across divides, or did it do more harm than good in an already fraught political environment? In a climate already marked by incendiary rhetoric and outrageous political stunts, what is the role of the artistic provocateur? In the same Facebook video, Krieger acknowledged that the exhibition’s theme was related to the political upheavals of 1948, when Israel gained statehood and established control of territory inhabited by Palestinians. “We all live in Arab houses,” Krieger said. He added, “Maybe Israel is stolen Arabic art.”

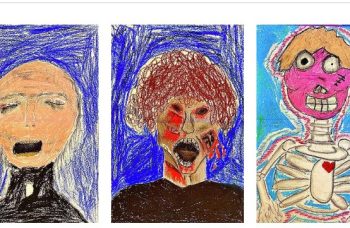

Image courtesy Omer Krieger