The Mori Art Museum in Tokyo is no stranger to exhibitions with bold ambitions marking anniversaries. In 2003, the museum punctuated their inauguration with an exhibition focusing on happiness. For their tenth anniversary, love and all its glory portrayed by the likes of Chagall and Kusama and Hatsune Miku was in full swing to note the occasion.

15 years on, however, the Mori has chosen a mood very different from previous anniversaries. ‘Catastrophe and the Power of Art’ evokes a range of emotions as it seeks to represent ‘what art can do in chaotic times where the future is uncertain’ as stated by the exhibition tag line. The exhibition comes as a response to global tragedies of recent decades. From the Great East Japan Earthquake in 2011 to the aftermath of Fukushima, there is no shortage of ‘inspiration’ for such an endeavor.

What ‘Catastrophe and the Power of Art’ chooses to do, though, is unique. Instead of focusing on the obvious, horrible, and deeply concerning issues the world has faced, the exhibition is highlighting how in the face of such difficulties, a crisis can shift from a negative to a positive. Through the process of recovery, creativity and imagination can be empowered. The Miro Art Museum’s press release notes that in the wake of recent events, ‘socially engaged arts’ have grown as a way to ‘potentially improve society’ and spark change within communities. Thus, the exhibition focuses on artworks that have a social message. Works by artists such as Yoko Ono and Miyajima Tatsuo have required audience participation emphasizing the collaborative effort that is recovering from disaster.

Over 40 artists and artist groups are represented in this momentous exhibition. Both Japanese and international artists, some are mainstays, like Isaac Julien and Mona Hatoum, while others are being shown in the Mori’s galleries for the first time, like street artist Swoon and those making their Japanese debut including Hiwa K and Helmut Stallaerts.

Separated into two sections, the exhibition seeks to document catastrophes that have riddled recent history in a different manner from mainstream news sources and social media. The hope is to offer future generations an alternative way to remember disaster and to promote the memory of those affected.

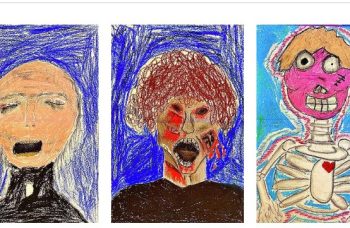

The first section, titled ‘How Does Art Depict Disaster? – Documentation, Recreation, Imagination’, represents the visual vocabulary often used to deal with disaster. From abstract works to fictional and realist, this section reaches from tangible disasters, like the violent acts of nature, to those less visible like the global financial crisis of 2008.

Section two, ‘Creation from Destruction – The Power of Art’ flips destruction on its head highlighting the positive, creative outputs that are sparked by devastation. These creations speak of hope and the work it takes to rebuild lives and societies. The Mori states that art, unlike medicine may be a slower acting remedy but that ‘it can serve instead as a long-term therapy for society.’

The tone of the large exhibition is heavy at the onset, particularly when compared to past exhibition themes. However, the Mori handles the topic of catastrophe in a thoughtful way that turns negative into positive. Thus, the exhibition exemplifies exactly what art has the ability to do in the aftermath of devastation.